The Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) is the leading provider of cost and carbon data to the UK built environment. Over 4,000 subscribing consultants, clients and contractors use BCIS products to control costs, manage budgets, mitigate risk and improve project performance. If you would like to speak with the team call us +44 0330 341 1000, email contactbcis@bcis.co.uk or fill in our demonstration form

Published: 29/07/2024

The new government’s approach to skills shortages in industries such as construction is to focus on upskilling workers already in the UK, rather than relying on overseas workers, and to grow the workforce through apprenticeships and Technical Excellence Colleges.

But construction has a long history of relying on migrant labour and, post-Brexit and post-pandemic, the industry is already struggling to meet resource demands in some sectors. The BCIS team considers the long-standing problem Labour has inherited and assesses the implications of its training and migration policies for future projects.

As the now infamous Co-op Live debacle neared its conclusion, ahead of the Manchester venue finally opening at the fourth attempt in May, the developer OVG’s CEO Tim Leiweke gave what the journalist described as an ‘at-times tearful’ interview to the Financial Times.

Leiweke described his shock at the shortage of skilled workers and, at a time when he could have been paying overtime and offering double shifts to get the project over the line, he said ‘we couldn’t find people to work, it was crazy’.

With Co-op Live its first major project in the UK, the skills shortage may have come as a surprise for American-based OVG, but it was probably less unexpected for those who’ve been around the industry long enough to know it’s far from being a recent occurrence.

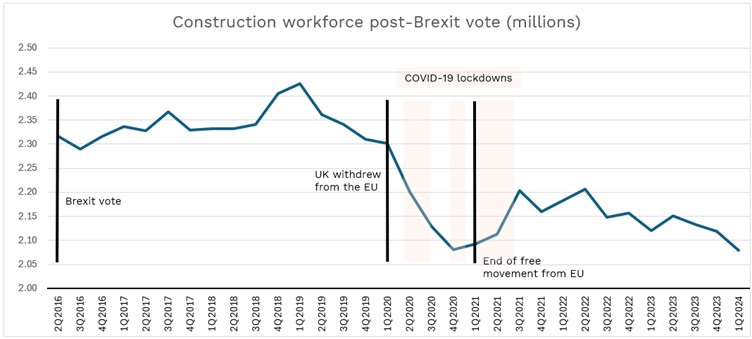

BCIS Chief Data Officer, Karl Horton said: ‘I can remember labour shortages being raised as an issue on projects at the start of my career 20 years ago, so it’s definitely not a new problem, but it has clearly been exacerbated by events in recent years. Post-Brexit we’ve lost the European labour that we have relied on in our recent past, and the domestic workforce has also declined since the pandemic.

‘At the same time, demand has also reduced as the industry has been hit by successive shocks including and since COVID – rampant inflation, sustained high borrowing costs, conflicts in eastern Europe and the Middle East.

‘While demand has been lower, the effects of a shrinking workforce haven’t been as noticeable, but demand will pick up at some point and then we will feel those losses more acutely. The direct effect of there not being enough labour to meet everyone’s needs is simply that costs will rise. As we saw with Co-op Live, it can also lead to project delays and potentially reputational damage.’

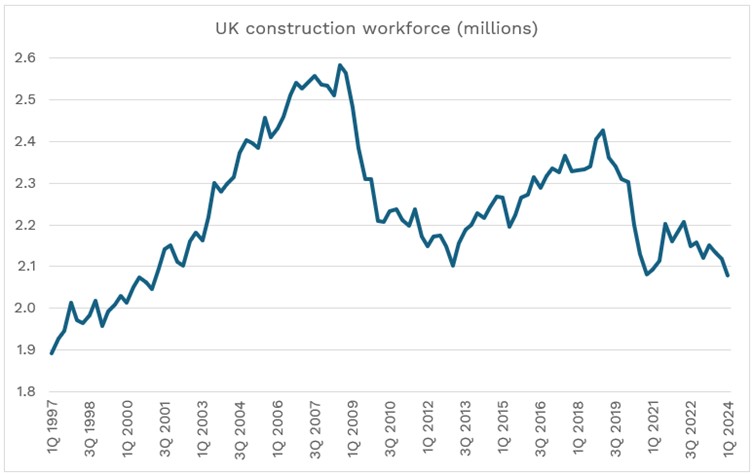

The construction workforce in numbers

Source: ONS

Total employment in construction stood at 2,078,926 people in 1Q2024, with a split of just over one-third self-employed to just under two-thirds directly employed. This was 10% less than the total number of workers in pre-pandemic 4Q2019. The number of self-employed workers decreased by 16.1% between 4Q2019 and 1Q2024. Longer-term, the construction workforce hasn’t really recovered since the financial crisis of the late 2000s.

Source: ONS

When the Conservative government published the updated National Infrastructure and Construction Pipeline in February, the Infrastructure Projects Authority (IPA) estimated an annual average of 543,000-600,000 workers would be required across different industry groups, including construction and engineering construction. It highlighted civil engineers and civil engineering operatives, plant operatives, and plant mechanics / fitters as roles most likely to see shortages.

At the time, the IPA offered the reassurance that the government was working to ‘address these risks and attract a reliable pipeline of skilled workers into the sector’. However, the only measure cited at the time was use of the Shortage Occupation List.

Since February, the Shortage Occupation List itself has been overhauled and the Immigration Skills List, now in its place, includes just stonemasons, bricklayers, roofers, roof tilers and slaters, carpenters and joiners, and retrofitters from the construction sector.

The latest data covering applications and granted visas for these occupations over the last three years demonstrates why reliance on it alone was never going to achieve the kinds of numbers needed, and it doesn’t cover many of the skills in which shortages have been cited.

| Bricklayers and masons | Roofers, roof tilers and slaters | Carpenters and joiners | |

| Number of applications 1Q2021 – 1Q2024 | 735 | 194 | 760 |

| Visas granted 1Q2021 – 1Q2024 | 606 | 130 | 641 |

Source: Home Office

*Retrofitters was added to the Immigration Skills List in April 2024 and is therefore not represented in the data.

Applications have predominantly come from South Asia since 2021 – workers from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh account for more than two-thirds of all applications in the three job roles in the table above.

Where are the shortages?

Reports of shortages have been widespread across the industry. Recent examples range from the London Homes Coalition, made up of major housing associations, contractors and specialist suppliers, this week reporting that the social housing sector in the capital will be 2,600 skilled workers short over the next five years, to the launch of the National Nuclear Strategic Plan for Skills in May, which set out how the nuclear sector needs to double its current hiring rate and double the number of apprenticeships by 2026 if it is to recruit for 40,000 new jobs by 2030.

Responding to Labour’s 1.5 million new homes plan, the Construction Industry Training Board has calculated an extra 152,000 workers would be needed to meet this level of demand.

Just prior to the dissolution of the last Parliament, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) called for the government to set out how it would address the fact that there is a lack of the necessary skills and capacity to deliver ambitious plans for major infrastructure over the next five years.

A report from PAC said: ‘Skills shortages in technical and engineering disciplines are set to worsen as gaps in the UK’s workforce are compounded by competition from major global development projects. Project management and design are also areas of concern, and skilled professionals in senior positions in particular.’

With the calling of the general election, the question of course went unanswered.

What is the new government planning?

The new government’s approach is not to rely on overseas workers – indeed it wants to lower net migration – but to ultimately upskill workers already in the UK and to improve working conditions here.

Labour’s manifesto pledged to ‘bring joined-up thinking, ensuring that migration to address skills shortages triggers a plan to upskill workers and improve working conditions in the UK’.

It said: ‘We will strengthen the Migration Advisory Committee and establish a framework for joint working with skills bodies across the UK, the Industrial Strategy Council and the Department for Work and Pensions.

‘We will end the long-term reliance on overseas workers in some parts of the economy by bringing in workforce and training plans for sectors such as health and social care, and construction. The days of a sector languishing endlessly on immigration shortage lists with no action to train up workers will come to an end.’

BCIS Chief Economist, Dr David Crosthwaite, said: ‘The degree to which Labour can support migration in the short-term at least, in order to meet the immediate needs of the industry, while also working on the longer-term ambition to grow the skills base in the UK, remains to be seen.

‘The trend of net migration figures over the last few years proved to be one of the more contentious issues in the run-up to the general election. Labour clearly wants to be seen as getting a grip on migration – both what is considered legal and illegal – but I think it’s short-sighted to disregard how important migrant workers have been for sectors like construction.

‘In an ideal world you would be able to deliver projects with a pool of locally available labour, but that hasn’t been the reality in the UK for some time, and it’s not what the industry has experienced throughout its history. From the great Victorian civil engineering projects which were built with Irish and Chinese workers, to the post-war reconstruction with labour from the Caribbean, and more recently workers from the EU, the UK hasn’t produced an abundance of home-grown workers.

‘The new government’s plan to boost vocational courses will take time to get workers on site and we’re short by hundreds of thousands. What the government decides to do with the Immigration Skills List and how it responds to the increasing reports of shortages in various sectors will be crucial.’

What then, of the government’s plans to produce the next generation of builders through apprenticeships and training.

Labour itself described the skills system in England as ‘confusing’ for young people and employers, and said the Apprenticeships Levy was ‘broken’ under the Conservatives.

Data from the Department for Education shows apprenticeship numbers have generally fallen in recent years in subjects linked to construction, planning and the built environment.

Apprenticeship achievements in Construction, Planning and the Built Environment subjects, England

| 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | |

| Intermediate apprenticeship | 6,616 | 5,548 | 4,989 | 4,406 | 5,156 | 4,848 |

| Advanced apprenticeship | 3,033 | 2,601 | 2,522 | 2,110 | 2,033 | 1,705 |

| Higher apprenticeship | 227 | 577 | 870 | 761 | 947 | 1,100 |

| All apprenticeships | 9,876 | 8,726 | 8,381 | 7,277 | 8,136 | 7,653 |

Source: DfE

Figures for chartered town planner apprenticeships, which are at degree level, show a total of 83 achievements in the last three years.

Shortages of workers and the challenges associated with recruiting and retaining apprentices have also been reported by members of the BCIS Scottish Contractors’ Panel.

Alan Wilson, SELECT MD and Chair of the Construction Industry Collective Voice (CICV), said: ‘Like the rest of the UK, Scotland has not been immune to skills shortages and apprentice recruitment challenges across the majority of trades.

‘Even in the electrical sector, where numbers of new entrants have remained consistently high, there is a fear that the numbers being recruited, over 900 per year, won’t replace those who are leaving the industry via natural wastage, or fulfil the additional demands which are being placed on the sector.

‘Overall, we face not only a skills shortage but a people shortage too. In Scotland, for the past few years more people are dying than being born and, from a high tide mark of 104,000 births in 1964, we now have a birth rate of less than 50,000, a 50% cut in the future possible workforce.’

BCIS Solutions Architect, Paul Burrows, who compiles the Hays/BCIS Site Wage Cost Indices said labour issues are a culmination of factors, starting with the lack of training.

He said: ‘I started my training at a specialist building college almost 45 years ago. Colleges like that no longer exist. The demographics of the Baby Boomers and subsequent generations have always been recognised as a problem which would occur as older workers retire and are not replaced. The lower numbers of young workers coming through apprenticeships and training courses simply compound the problem.

‘Adding to the already difficult situation, we have had very low real-wage growth since 2008, making construction a less attractive career choice. Hourly rates for some grades of unskilled workers are now being pushed upwards by minimum wage legislation, rather than the normal progress of pay settlements.’

Part of Labour’s plan is to ensure the minimum wage is a genuine living wage. It also said it will change the remit of the independent Low Pay Commission to account for the cost of living and remove age bands, so all adults are entitled to the same minimum wage.

In and of itself, it’s probably not the incentive that will lure droves of young people into construction apprenticeships.

More specifically, Labour’s main method to boost further education and apprenticeships is to establish Skills England, a body that will bring together businesses, training providers and unions with national and local government to ensure there is a workforce to deliver the Industrial Strategy. Further, it wants to formally work with the Migration Advisory Committee to make sure training in England reflects the overall needs of the labour market.

The new government has also promised to transform Further Education colleges into specialist Technical Excellence Colleges, which will work with businesses, trade unions, and local government to provide better job opportunities. In place of the Apprenticeships Levy, it said it will create a flexible Growth and Skills Levy, with Skills England consulting on eligible courses to ensure qualifications offer value for money.

Dr Crosthwaite said: ‘Aligning the needs of the industry with education provision is sensible but there’s an unavoidable lag from getting more young people into apprenticeships to getting them on site Even the establishment of Skills England is set to take place in phases over the next year. We absolutely need a long-term plan, but the government can’t ignore what’s right in front of them now.’

With all of Labour’s promises to boost the economy and ‘get Britain building’ it’s easy to focus only on what the government can do to support the industry, but it’s important not to overlook what part the industry has to play in its own future too.

Horton said: ‘As much as the government can help to create the right training environment, there’s also an obligation on the industry to demonstrate its attractiveness to the next generation of workers. Construction companies need to invest in training and they also need to have the patience to see it through.

‘The added complexity is that the industry doesn’t just need to find workers with the skills for today’s industry, it needs to plug the gaps as well as adapting to where the industry is going and the new skills that are going to be required in years to come.’

The transient nature of the construction industry, with many jobs being project-based or seasonal, must also be taken into account.

Dr Crosthwaite said: ‘Construction tends to self-balance, with workers moving to where the work is. When house building output decreases, workers shift to other projects.

‘The era of tier 1 contractors directly employing all their labour is over. There’s been a move towards more flexible working arrangements, allowing capacity to be adjusted as demand fluctuates.

‘After the pandemic and recent economic changes, there’s no incentive for companies to invest in directly employed labour due to the unpredictability of the future. Uncertainty has become the norm.

‘This self-balancing system works well when labour reductions match decreased demand, with resources simply shifting around. The key question for the new government is, taking the sum total of their plans and policies to boost the economy through the built environment, is there a workforce big enough to do it all? As things stand, I’d say not.’

To keep up to date with the latest industry news and insights from BCIS, register for our newsletter here.