The Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) is the leading provider of cost and carbon data to the UK built environment. Over 4,000 subscribing consultants, clients and contractors use BCIS products to control costs, manage budgets, mitigate risk and improve project performance. If you would like to speak with the team call us +44 0330 341 1000, email contactbcis@bcis.co.uk or fill in our demonstration form

Published: 24/07/2025

Delays to Gateway 2 approvals for higher-risk building (HRB) work is a problem that even the newly launched inquiry into building safety regulation cannot wrap up fast enough.

Developers have reportedly been waiting up to one year for the green light and the impact on project starts and costs is inconvenient at best. Reforms to the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) announced in late June, which include boosting the BSR’s capacity and moving the regulator from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), are a good start. If combined with better quality applications for new HRB work, they could make a real difference.

Whether process change will serve government housebuilding goals as hoped, however, remains to be seen.

Speaking at the latest committee meeting for the new regulatory inquiry, Dame Judith Hackitt, Chair of the Building Control Independent Panel, argued that reducing delays at Gateway 2 – a checkpoint at pre-construction where the BSR decides whether applications for HRB work meet regulatory requirements – must be a shared duty between developers and the BSR(1).

She suggested a historic lack of collaboration between the parties was at fault as much as the inadequacy of applications being submitted. Other attendees shared industry frustrations over the BSR’s ambiguity on the detail required from developers.

As if on cue, new guidance on submitting applications was published by the Construction Leadership Council (CLC) less than one week later – the product of collaboration between the CLC, industry stakeholders and the BSR. It provides baseline principles for submitting and assessing building control approval applications with an emphasis on bringing the quality of submissions up to scratch(2).

Its arrival is undoubtedly well-timed.

New data published by the HSE, acting as the current BSR, show that delays on building control approval applications increased by 443% in 1Q2025 on 1Q2024(3).

Looking at the available data, rapid growth in the BSR’s caseload was a key driver.

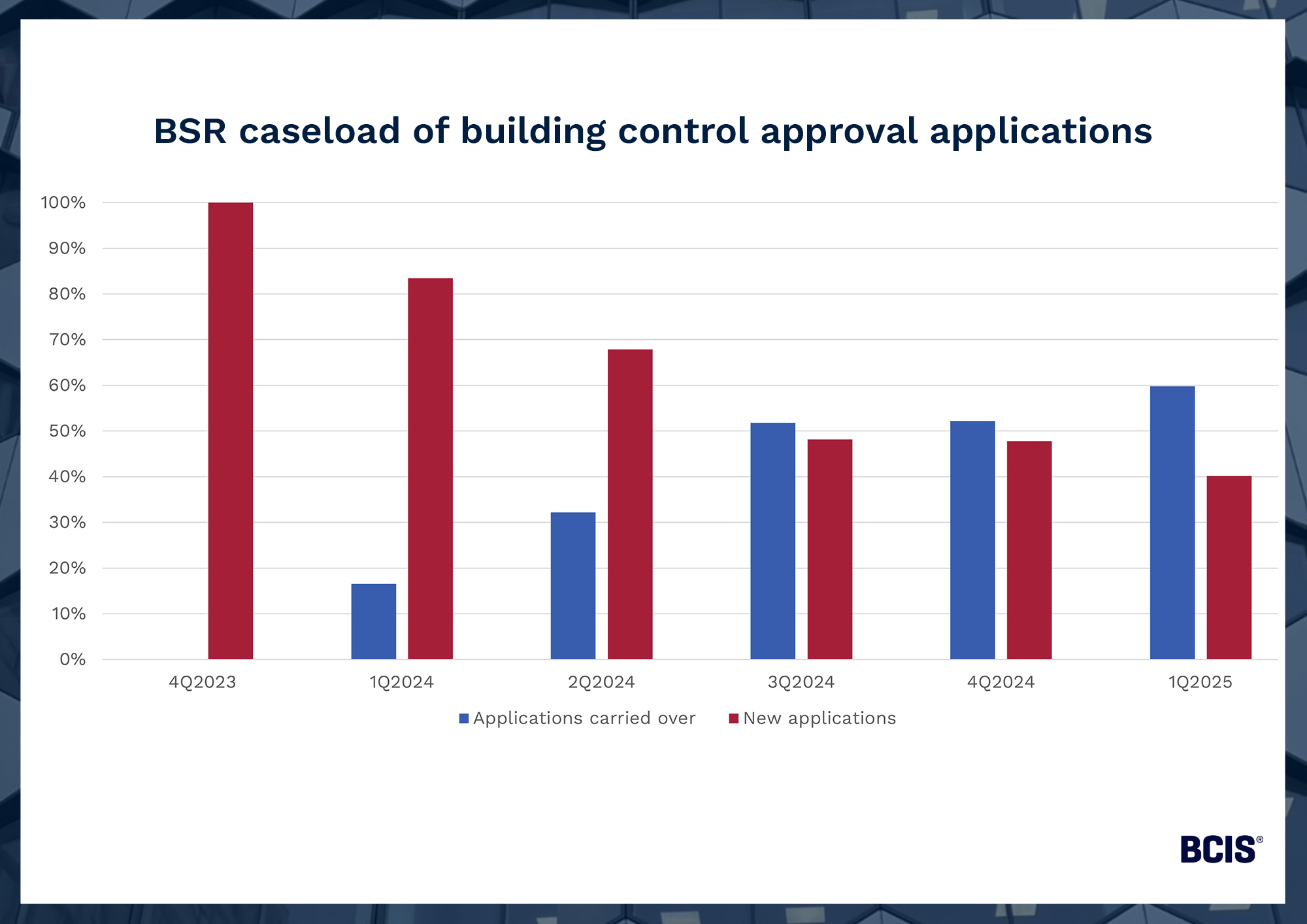

Since the BSR began processing applications for HRB work in 4Q2023, the backlog or proportion of open applications carried over each quarter has quickly overtaken new applications received.

Source: Building Safety Regulator

By the end of 1Q2025, almost two-thirds (59.8%) of the BSR caseload comprised outstanding applications submitted in previous quarters.

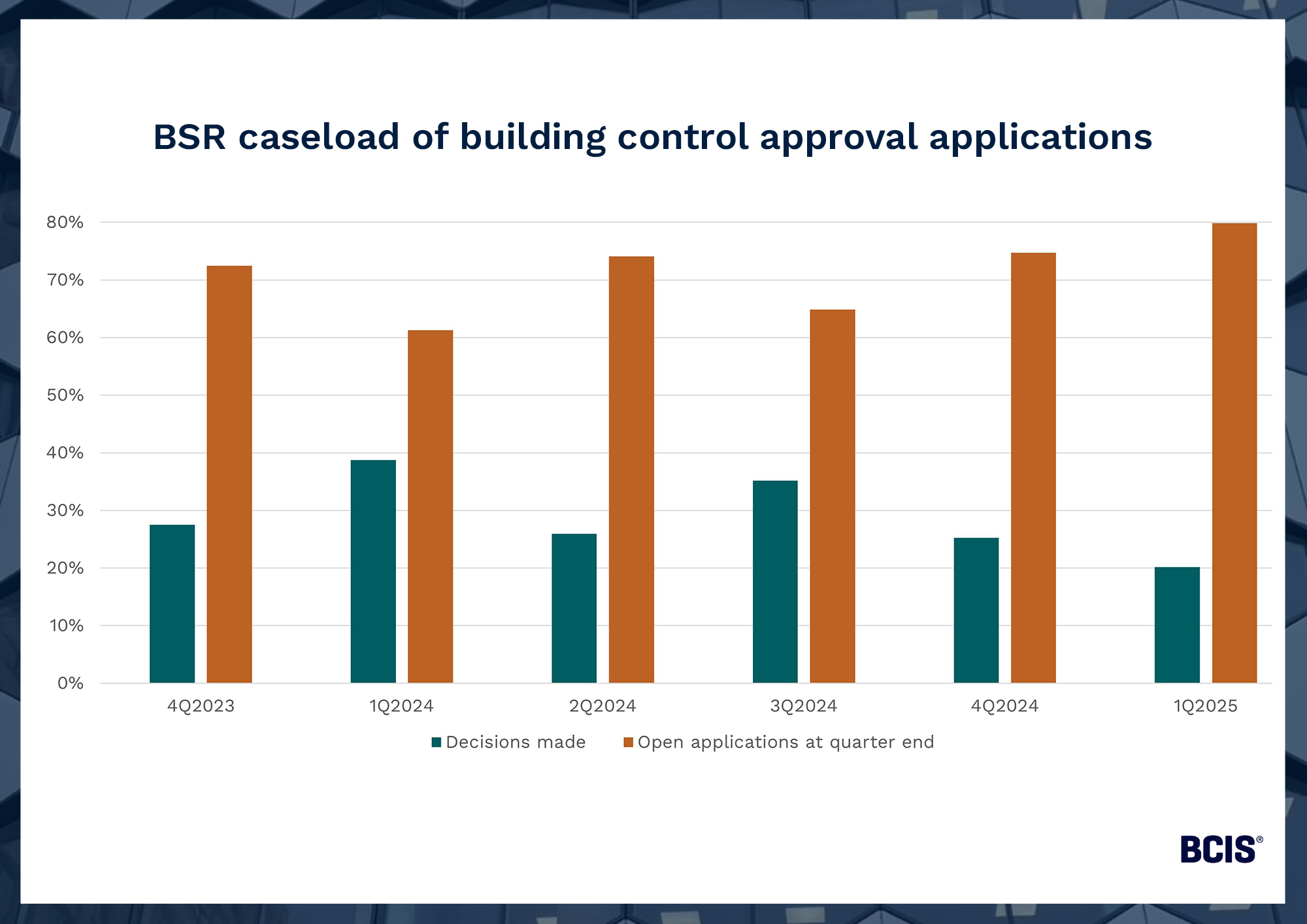

Decisions made on applications also fell to the lowest rate on record in this period. Only one-fifth (20.1%) of 1,276 applications received a decision in 1Q2025, leaving 1,019 still awaiting an outcome at the end of March.

Source: Building Safety Regulator

Regardless of fault, the data point conclusively to a dysfunctional system.

Fortunately, things are now moving in the right direction.

Government reforms include a ‘Fast Track Process’ that will improve the review of applications by increasing building inspector and engineer capacity in the BSR(4).

The BSR will also operate under a newly established board in the MHCLG as part of plans to establish a single construction regulator. The government’s hope is these reforms will cut down waiting times and help to accelerate housebuilding activity.

The newly released guidance on submitting high-quality applications should also serve as a turning point. Of the 257 application decisions made by the BSR in 1Q2025, 29.5% were declared invalid – those that do not pass the validation process or are inactive and have not received a decision.

However, addressing delays is one thing. The ability for process reforms to fulfil the government’s 1.5 million new homes target is a different ball game entirely.

Local authorities in urban areas, where development space is limited, will likely require high-rise residential developments to meet housebuilding targets. Doncaster, Oxford and Warwick were among several cities that saw significant increases to housebuilding targets last year(5).

According to regulation, any building of at least seven storeys or 18 metres in height, and/or contains two or more residential units, is considered a HRB and must therefore be assessed by the BSR and pass building control approval at Gateway 2 before work starts.

In other words, ongoing delays could ensure the government’s target is not met.

There’s also no guarantee BSR reforms will significantly reduce the application backlog at the pace needed. As it stands, the current backlog is not going to be cleared overnight.

Other hurdles include rising costs for developers.

As of April, the cost of submitting building control approval applications increased by 5% to £189 per submission(6) and, as of autumn 2026, residential developers will be charged per square metre of gross internal floor space on HRB work under the Building Safety Levy.

While established to elevate building safety, the risk is these measures could disincentivise developers from prioritising certain projects that benefit the government’s housing target.

Housebuilders carefully control housing supply in a way that protects their commercial interests and it’s unlikely smaller businesses will put their profits on the line just to ensure 1.5 million homes are built.

In the past few months, the effects of delays at Gateways 2 and 3 have been keenly felt with BCIS panellists flagging the impact on resource management.

It’s impossible to say whether the long-term impacts of delays will be fully resolved before more regulatory costs are introduced, but their continued presence remains a significant cost burden.

Incentives aside, the feasibility of reaching the housebuilding target already seems unlikely. EPC registrations data show 186,600 (rounded to the nearest 100) homes were built between 9 July 2024, the first meeting of the current Parliament, and 15 June 2025.

To hit their target, the government must average over 300,000 new homes per year, which is a big ask without a significant regulatory backlog.

At this stage, a yellow brick road to 1.5 million new homes is still just a dream.

To keep up to date with the latest industry news and insights from BCIS, register for our newsletter here.

(1) – Parliament live – Building Safety Regulator – here

(2) – Construction Leadership Council: Building Control Approval Application for a new Higher-Risk Building – here

(3) – UK Gov – Building Safety Regulator building control approval application data October 2023 to March 2025 – here

(4) – UK Gov – Reforms to Building Safety Regulator to accelerate housebuilding – here

(5) – BBC – Where does the government want 1.5 million new homes? – here

(6) – Construction news – BSR set to hike application charges by 5 per cent – here